In this unit, you’ll complete the following tasks: Create a GitHub Action to implement a deployment pipeline Increment the coupon service version in the Helm chart, Verify that the changes were deployed to the AKS cluster, Roll back a deployment…

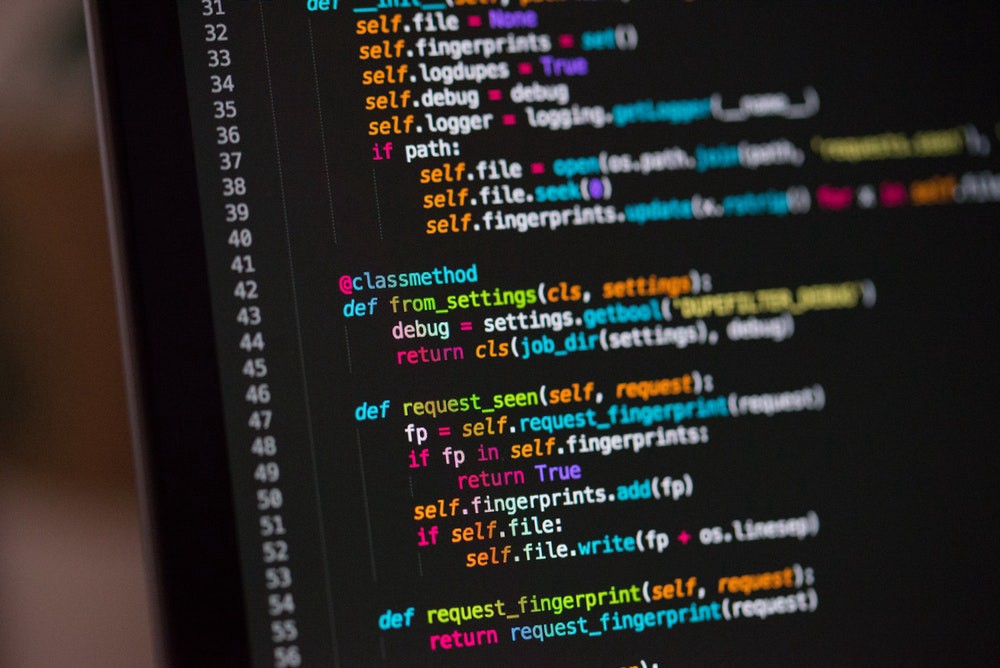

Category: Code

3 Sites to Learn to Code – for Free 2022 – Online

1. Codecademy

Learn the technical skills you need for the job you want. As leaders in online education and learning to code, we’ve taught over 45 million people using a tested curriculum and an interactive learning environment. Start with HTML,…

3 Best Web Development Tools

Web development is one of the most sought-after professions of the 2020s. You can easily earn more money in this profession. Developing the website requires HTML, CSS, web hosting and programming knowledge as well as some web development tools. Today …

Replit specialized IDE

Welcome back to this edition of the Replit post! In this edition:

- Build your own Replit

- The July Changelog

- Our summer hackathon!

- How to build an alexa skill

- Goodbye and emails

BTW, Replit is searching for engineers and business folks …

What is Software Development Models | Software development life cycle (SDLC)

When developing software you need to focus on various things. Writing code is not your only task though it is still vital. Basically, you should answer the following questions: what you’re going to do, how, using which methods, and why. …

How to create a pull request on GitHub

You’ve learned how to create a pull request when there’s guidance – either in a pull request template, or in a CONTRIBUTING file. But what if a project doesn’t (yet) offer that guidance and documentation on conventions?

Describe your changes

…What is Markdown?

Markdown exists to shield content creators from the overhead of HTML. While HTML is great for rendering content exactly how it was intended, it takes up a lot of space and can be unwieldy to work with, even in small …